“Whoa Dada, look at Sibs go! Cause see?” hollered the squirt from behind me.

The dog’s behavior had changed, to be sure, but the difference between ‘before’ and ‘after’ wasn’t (if one stuck to the observable facts) really that pronounced. Her turns had become sharper and more frequent. She’d accelerated a touch and added a bounding quality to her stride. Her snuffling had shifted from curious to urgent. And, of course, there was her tail gone wild at chopping and whirling. That’s about it.

But what’s seen is only a fraction of the evidence. The bulk of such a shift can only be felt. It’s like the sensation at the top of a roller coaster, balanced for a heartbeat between climb and plunge. Or the live-wire jolt in the instant she signals you to move in for the kiss. Or the collectively held breath of a packed arena that knows, heart and soul, the game-winning three-pointer, just released at the buzzer, is headed for the bottom of the net.

The birds aren’t flying, yet, but something unavoidable, concrete and ineffable has been set in motion. It’s happening. Now. Even the six-year-old feels it.

I might have answered him with a “Here we go!”, or “Buckle-up!”, or simply “Dog’s birdy!”, if hadn’t been racing through the sage for position. But, then again, maybe not. What good are words, after all, in moments like that?

“You’ve got too many shotguns not to have a bird dog,” Steven told me. It was half admonition, half challenge, to someone with no real experience with bird dogs. Let’s be clear: it’s his fault.

He wasn’t wrong about the shotgun part though. I have a lifetime of fond memories of shooting clays with my dad. Once, when I came home from college too cocky, he restored my humility by trouncing me with his perfect round of skeet. I might have broken half of mine. Maybe.

He liked shotguns and obviously shot them well. But as his eyesight faded over the years, I inherited a couple that fit me, with the understanding that they would be used often, and paid for in stories. When I met Steven, they were only getting used occasionally.

I was also dogless at the time, so I probably needed a little chaos and mayhem in my life. Right?

After phone calls to friends to discuss their favorite dog breeds, hours of internet research, weeks of discussion with my wife, guilt over not adopting a shelter dog and months of vacillating, I found a breeder, not far from us, with a new litter. One dog unsold.

We settled on a day for me to come out and visit and I climbed into the truck for the trek north. I’ll admit I showed up with a bit of a chip on my shoulder, sort of daring the guy to give me a reason not to spend my money. I was polite but I was looking for a reason to write the operation off and say no to a big change in my life. Still, I did what you’re supposed to do. I asked questions, I checked the place out, and I met the parents. As if to reinforce a stereotype, the breeder was a bit reticent. Not impolite, just taciturn. He answered every question I had. Confident. Clear. Concise. Compelling. Never a salesman.

Every single dog in the pen was clean, active and happy looking. Their bedding was clean. The floor around the pen was clean. And they were cute with a capital C (italicized and underlined for good measure). Intellectually, I knew they’d be cute and was ready for it. Of course puppies are cute, it keeps us from eating them when they wreck the rug. Being cute is what they do, so for a while we watched them do it. I may have giggled, but I doubt it. I’m a pretty serious guy.

At some point I asked about his claim that every dog would point and retrieve before it left his kennel, and he offered a demonstration. There was no way I was going to say no to that.

He reached in and confidently picked out a puppy. How he could tell one dog from another in that squirming pile of puppy flesh was a mystery to me, but he seemed to know his business and picked out the only dog unspoken for. He set her on the floor and she flailed a bit as he set her down between us. Then, true to puppy form, she started to stagger off like a drunk in pursuit of a shiny bottle of smart juice.

He steadied her with a soft word and a hand on her chest, pulled off a leather glove and waved it in her face to get her attention. Once her eyes had focused on the target he lobbed it about ten feet away and let her go to it. She took off like a wobbly dynamo, a ton of cute in a six pound frame. She picked up the glove, shook it once, and started back toward us at a proud trot, head held high, with the glove almost entirely hiding her tiny body.

At that exact moment I was a goner. I just didn’t know it yet.

We talked some more. I met the dam and saw her work. We discussed guarantees, health certifications, shots, shotguns, worms, vet visits, parvo, training options, theories and support. At some point I realized I was buying a dog and should probably let the breeder know. He probably already knew. He took it well.

On a good day, I live about two hours from this kennel. With snow on the ground, some ice on the roads and an uncertain puppy bladder we made it home in three. We stopped twice for water, a pee break and to stretch her tiny puppy legs. I’m pretty sure I also wanted to watch her walk around and sniff things. I was smitten.

In hindsight, I was a goner from the get go, a sap with no power to resist puppy cuteness coupled with a genuine desire to own a bona fide birddog — a deliverer of ducks, retriever of roosters, pointer of pheasants, chaser of chukar and mauler of mergansers (and general badass with birds I couldn’t come up with cheesy alliterations for). Now four, she’s all that and more — companion, conscience, comic relief, mood adjuster.

I couldn’t be happier, though my elk hunting time has suffered a bit.

Which leaves only one question. What is the proper shotgun to dog ratio?

“I want the sides… and the bottom…,” said Mr. Daniel, indicating plumb and level right-angles with his hands. “Twelve inches by a foot. Follow the string. See you at lunch.” Then, with no further instruction or explanation, he handed me a worn spade, turned, walked back to his air conditioned Buick and drove away.

I was eighteen and every bit as ignorant as that age would suggest. But even I could see, as he maneuvered his big sedan past his idle backhoe, that Mr. Daniel had no need of my labor whatsoever. He’d hired me for the summer as a favor to my father. Digging tie-line ditches for his next warehouse, he figured, was as good a way as any to keep me busy and out from underfoot. For my part, I was so broke that I couldn’t even pay attention, much less my fly shop tab. I needed the work in more ways than one. So before he’d made it to the edge of the clearing, I made sure he could see me shoveling in his rear-view.

I stayed bent over that shovel from eight until noon, stabbing and scraping my way through the rocky red clay, alone but for the drone of cicadas and the mounting heat. When the black Park Avenue reappeared as promised, I was flush with sun and the self-satisfaction that comes from hard labor and visible results. The feeling was short lived.

“Hot damn son, you never work a shovel before?” asked Mr. Daniel, handing me a brown paper lunch bag and a look of disdain. He didn’t wait for a response before loosening his tie, rolling his sleeves and relieving me of the tool.

“Time I was your age, I had a PhD in shovelology,” he explained stepping his polished wingtips into the fresh turned dirt. “I said square… unh… and square… unh. See that? Watch me now. Square… unh, and square… unh,” he continued, punctuating the lesson with clean, precise punches of the spade and transforming my sloppy trough into a proper trench. “Can you do that?”

“Yes sir,” I said, not entirely sure that I could.

“Good. Best eat-up now. Lots a work yet,” he said, appraising me with frank but forgiving eyes.

He was right. There was a lot of work to be done… on that job, and the next and the one after that. Mr. Daniel owned half of Culpepper County as best as I could tell, and whatever unpleasant task needed doing that summer, at any of his numerous enterprises, I was the boy for it. More often than not I took my daily marching orders from one of his various foremen or managers, but every now and again I’d report in the morning to find Mr. Daniel waiting for me.

“Git in,” he’d say, gesturing to the Buick. Those were always the most unsavory assignments. They’re also the ones that have stuck with me. Mr. Daniel was a busy man. That he took the time to personally direct my menial efforts struck me even then. By some miracle I was smart enough to take notice.

The big takeaways from that summer sunk in readily enough – there’s no shame in dirty hands, but its good to have options; there’s no substitute for showing up and working hard; nobody worth their salt is too big for a small job; if it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. But it’s not just the big picture concepts that I’m grateful for.

Every inch of spadework in that long ago ditch becomes a blessing when it’s time to dig a grave for a friend.

There’s just no earning unconditional love. We feed our dogs, shelter them, take them on adventures and rub their bellies, but in the end, at best, it’s a pretty lopsided relationship. How do you thank the animal that ignored your faults and saw in you, without exception, the person you wish you were? What do you offer? You laugh and recall the good times. You help them die peacefully. And if you’re fortunate enough to have been taught how, you pour your sweat, and your tears, and your energy into the earth until the sides are square, and the bottom is flat. It’s not enough. There is no enough. But it’s what you have to offer. So you do.

Happy hunting in the Great Beyond Sugar. Rest in peace.

“You got a beer?” Grady asked quizzically as he nibbled a fry.

I nodded, taking a sip of a cold Rainier.

“I didn’t know they had beer here,” he responded, genuinely surprised.

The flicker of a neon Miller Lite sign illuminated our table. Three truckers sat at the bar. One had just picked up a load of calves. They were 48 pounds light but he took them anyway. The bartender wore a hoody with the sleeves pushed up. Tattoos adorned her arms and pink streaks accented her dirty-blonde hair. She called Grady hon and brought him a Shirley Temple in a paper cup.

I gazed at a the antlers on the wall between bites of greasy burger. An old, varnished, heavy-beamed bull, with weak fourths and good fronts, barely fit in the corner. He was competing for space with a slot machine and low ceilings. Cobwebs and orange sequins were draped throughout the joint in preparation for Halloween.

“I wish we’d have shot a bird today.”

“Me too,” I responded.

There was no school. After a day working at home, and shuffling the kids between different sets of parents in an effort to help all of us get some work done, I conceded to going hunting. We loaded the dogs, snacks, and a shotgun.

Despite good habitat, conditions, and the discovery at the sign-in box that we were the first hunters in days, a long walk yielded only one flushed hen. It was nearly perfect for us. Finishing close to dark we stopped at the roadside bar for a quick dinner, before making the hour long drive home. The little man fell asleep in the truck. I slung him over my shoulder, carried him into the house and tucked him in for the night.

“Has Matthew not discovered the meat trough at the Piggly Wiggly?” asked my Father-in-law.

His question, shrugged off with an appreciative laugh in the early season, felt far less rhetorical weeks later when the alarm clock wailed, once again, at 4 a.m. The predawn cold, I knew from repetition, would demand its own answers shortly. The steep climb would do some asking too. Do you really need to be doing this?

There are easier ways to fill the freezer. Cheaper ways too. And though I’m fond of saying “We rely on the meat,” it’s a luxury of circumstance that I even get to think that way. In truth, we’d be just fine without the annual elk. The frozen toes aren’t strictly necessary. Nor the time away from family or the backlog of shelved obligations.

Easier ways indeed, and they multiply in the mind with each quad-scorching uphill step and each gust of wind-borne snow.

Easier ways. No doubt about it.

Of course, easy and worthwhile are different species. Thankfully they keep selling me tags for the latter.

We were a couple hours into a five day river trip when the current grabbed his rod and pulled it under. I looked behind the boat just in time to see it sink to the bottom. There would be no recovery. You would think the rod was an heirloom based upon the tantrum that followed. To the three year, old it didn’t matter that it was a freebie from a local thrift store. It was his rod and our primary plan for keeping him occupied while floating.

Forty five minutes later a sense of decorum was restored in the boat. With emotions a bit frayed my wife quipped that we might have been better off leaving my son behind. But we were committed now. In camp that evening he nearly broke a tent pole in half (it wouldn’t have been his first) and he had found a fly swatter that was sufficing as an implement of destruction in place of the lost rod.

Just after dinner he declared he needed to use the bathroom…now. A quick glance from my wife made it clear I was on duty for this one. We were on a permitted river with established latrine’s. Someone later reminded me that the ranger had asked if anyone in our group had mobility problems when we selected this campsite. I didn’t recall that question, as I ran with my son under my arm up the steep incline. Maybe a hundred feet up I was gassed. Sweating profusely I put my son on my shoulders and continued upward.

Once comfortably on the toilet, with me doubled over nearby, my son looked at me and said “Dad…I love the Smith River”.

“Elk grazing the meadow at dusk,” stage-whispered Steven just before our trail emerged from the timber. “Just like Grandpa taught me!”

He wasn’t exactly joking, but he wasn’t calling his shot either. Mostly, the remark was a good-natured, gallows-humor response to long, fruitless, hours afoot in challenging terrain — an attempt at brushing away the dark cloud of what-ifs and shoulda-couldas that had begun to threaten our frozen march back to camp. Mostly, but not entirely…

Because five strides farther and the upper-meadow came into full view, complete with its lone grazing cow. It’s a miracle she didn’t spook at the flash of our shit-eating grins.

“Doubt she’s alone,” whispered Alan, giving voice to our new-found collective focus, and the shared belief that genuinely solo cow elk are far rarer than the common variety (seemingly solitary cow elk surrounded by invisible companions). We settled in to watch for the next appearance.

We glassed the treelines, scrutinized the shrubbery and examined every dip and swell of the park, but as the last of the comfortable shooting light dissolved, she remained a party of one.

“But a helluva a call right?” said Steven, high on the close-encounter and no longer bothering to keep his voice down as we strode, exposed, through the open.

“Seriously! Too bad she was …”

The body is quicker than the mind in certain situations. If you lay a hand on a hot stove, for example, your arm will remove it before your brain has even felt the pain. Or, hypothetically speaking, if 700 pounds of muscle, antler and churning hooves erupts from the tall grass you were about to stroll into, you may drop to a knee and shoulder your rifle, green plastic army man style, mid-sentence.

At least I assume that’s how I arrived in that position with Steven, crouched next to me, whisper- yelling in my ear “Bull. Bull. It’s a bull.”

The elk crossed our path at a full sprint, digging like a greyhound for the opposite treeline. There was just enough light left in the witching hour to make out the clenching of his shoulders, back and rump through the scope. And then he was gone. The vibration of his hoof-beats resonated through the ground a second longer.

“Holy shit”, I said when my breath returned.

“Wow…. Why didn’t you shoot him?” asked Steven with a chuckle.

“Yeah… not really the shot I’m looking for.”

“Whatever. Your loss. For the record, though, Grandpa woulda dropped him.”

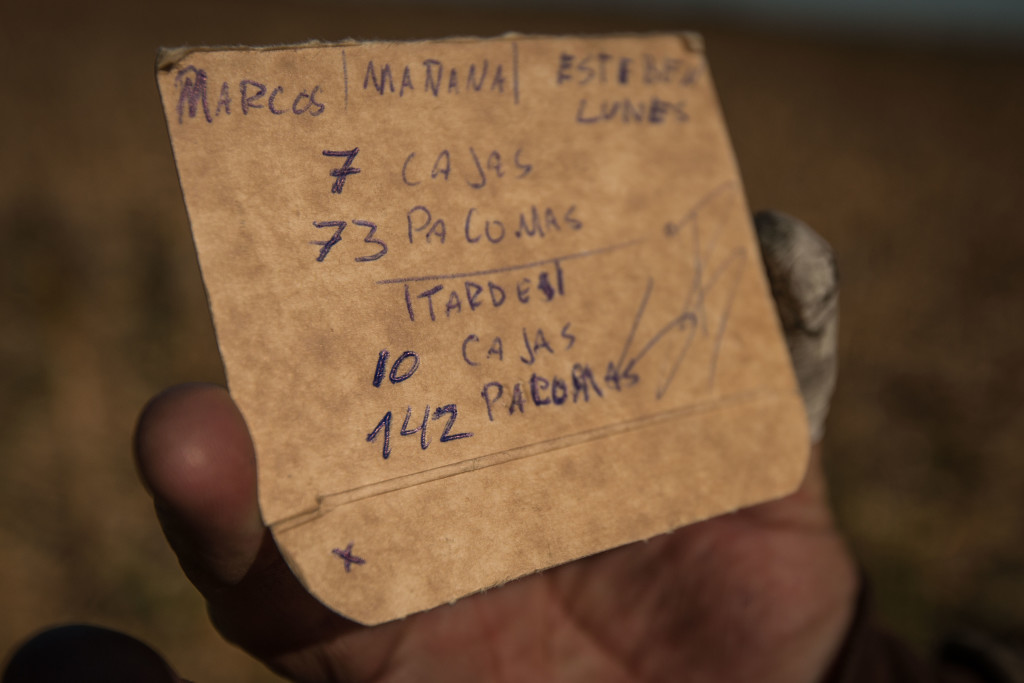

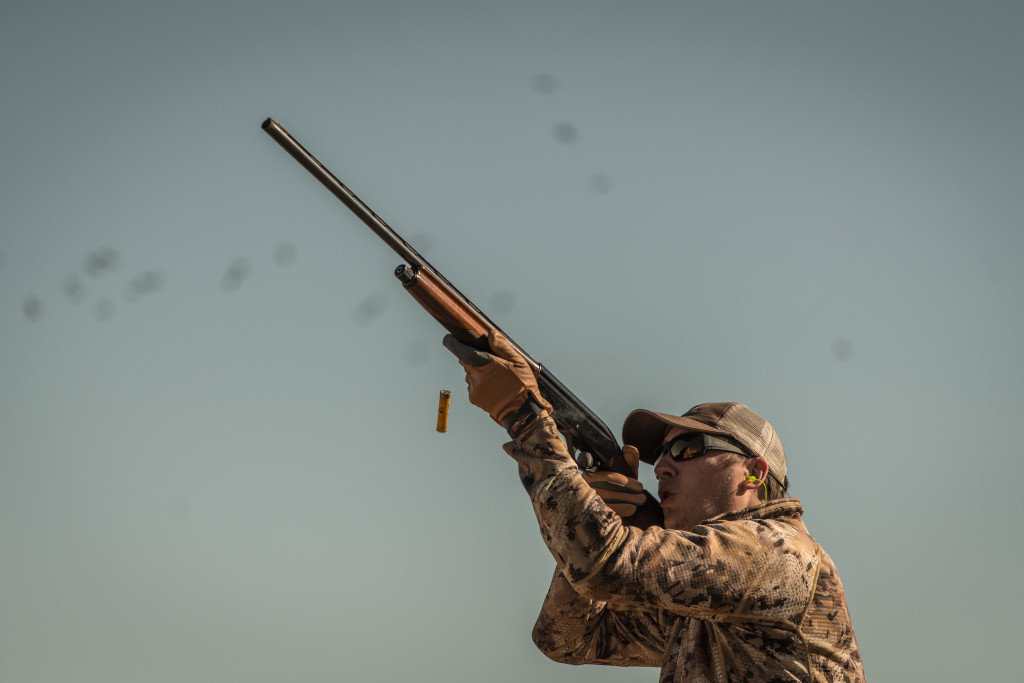

We set up on the edge of a five thousand acre roost. It looks like an impenetrable fortress of thicket 10 to 20 feet high. The roost is surrounded by cropland and is home to 50 million doves. Regionally the doves are considered a plague.

We stand our ground and aim to hold our own. The doves fly constantly. I hit the first couple and then miss nearly a box worth. Slowly I get into the groove. Swing, lead, shoot, repeat. I exchange the shotgun for camera and enjoy the show. Over two and a half days, with my primary focus on photography, I accidentally killed 500 doves. Those focussed on shooting would shoot more than that per day. A good shot, eager to stack up numbers, might try to join the elite yet attainable 1,000 bird/day club.

Guns are barely up to the task. The lodge swears by Benellis and Berrettas and supplies them to clients. A full time gunsmith is on staff, each gun is inspected and cleaned twice a day. Guns last two seasons. They have to import 40 new guns each year.

Guns are barely up to the task. The lodge swears by Benellis and Berrettas and supplies them to clients. A full time gunsmith is on staff, each gun is inspected and cleaned twice a day. Guns last two seasons. They have to import 40 new guns each year.

A semi truck arrives each Friday and unloads 70,000 rounds of ammunition. Fiocchi has a plant in Argentina. Maers & Goldman has an exclusive agreement with Fiocchi to purchase every 20 gauge shell produced in country. That adds up to nearly 4 million rounds per year.

The lodge is open every day of the year, except between Christmas and New Year, hosting about 20-30 guests at a time. With guests shooting an average of 50% that leads to approximately 2 million doves killed per year. A crazy number that barely puts a dent in the population.

The lodge is open every day of the year, except between Christmas and New Year, hosting about 20-30 guests at a time. With guests shooting an average of 50% that leads to approximately 2 million doves killed per year. A crazy number that barely puts a dent in the population.

We ate doves every night, prepared in ways I never imagined, and they were delicious. However, in the short time I was there most went uncollected from the fields. As we neared the end of each shoot hundreds of raptors, hawks, eagles, and vultures, all slightly different from any species I had seen before, descended on the fields to devour the doves in a mass feeding frenzy. The roost is also home to Pumas that creep out and take their share. It looks as if an entire food chain has developed from the dove hunting industry.

The owner and I discussed lead and it’s effects on the soil, water, and raptors. As one of the largest lodges in the country they are working with the Government to sample all of the above for potential negative effects. They are open to making changes if they’d improve the sustainability of the operation. Moving away from lead in the near future seems likely. But it’s not as simple as going to the store and buying steel. An entire supply chain, complete with international borders, needs to be altered.

The owner and I discussed lead and it’s effects on the soil, water, and raptors. As one of the largest lodges in the country they are working with the Government to sample all of the above for potential negative effects. They are open to making changes if they’d improve the sustainability of the operation. Moving away from lead in the near future seems likely. But it’s not as simple as going to the store and buying steel. An entire supply chain, complete with international borders, needs to be altered.

Picking up shells we all had smiles on our faces and while shaking our heads in disbelief. The math, logistics, and volume of it all is mind numbing. Eyes wide open, I was full of questions, simply curious to understand how it all works. A couple days satiated me. But if you love wing shooting, like to pull the trigger, and want to wash it all down with a glass of Malbec, their is nothing comparable to Argentine dove hunting.

Someone once explained to me that there are three stages to any elk hunt.

Stage 1: Finding the Elk

Most years, upwards of 90% of my time afield is spent in stage one, even more if you factor in the time spent scouting and pouring over maps in the off-season. But that’s ok. These are the quite hours before dawn, glassing a basin from a distant ridge, or staking out a likely meadow. The world is full of possibility. There is an elk in each shadow, and behind every tree, you need only look to the right place, at the right moment and know it when you see it. This is when you lose yourself for hours to the little wonders of the mountain and when the anticipation builds with each carefully placed step in the dark timber. Because the next step could be the step, the one that brings you to the twitch of an ear, or the glint of sun off antler; the step from stage one to…

Stage 2: Acquiring the Shot

… in which the world is instantly rewritten with a pen of adrenaline and the ink of all five senses. You are in elk now, among them, no longer a seeker, but a predator, and hungry. Your heart is in your throat, but it can’t choke off the torrent of sounds and smells and tiny clues that have swallowed you whole. The aches and pains of nights on the ground and days in the hills have vanished, taking with them every other silly distraction … the state of your retirement portfolio say, or next week’s schedule, or breathing. Because you are moving now, making decisions moment by moment – life and death decisions based on the taste of the wind and how it sits with your gut –all consumed with closing the gap, finding an angle and…

Stage 3: Making the Kill

There are no more decisions, only knowledge. You know that there is no shot, then, just as certainly, that there is, and that you are taking it. Maybe you say a prayer. Maybe it’s all been your prayer. Then with a bang that you never actually hear, it’s done.

I wish I could remember who pointed out the stages to me. I’d like to give credit where it’s due. Whether the process unfolds over the course of days, in a matter of seconds, or is derailed mid-cycle, thinking of it as such provides a tidy frame in which to arrange the experience’s constituent shards. Otherwise it might be lost to me forever.

Or, with no boundary to contain it, I might be lost to it.

Of course that’s probably what I was after in the first place.

Jeremy pulled an elk quarter from a cooler in the garage and set it on the kitchen table. I sipped a beer as he butchered the meat and told me the story of the calf he’d killed two days earlier. He’d wanted to check out a new area. It seemed unlikely, but he’d gotten into elk on his foray.

Tim poured me a cup of coffee. Wearily he pulled out a chair for himself. He’d spent the previous two nights packing elk off the mountain. A shot late in the day, followed by a long tracking job, had forced him to leave the meat for a night, and half of it for a second. He hadn’t been too worried with the area largely devoid of bears. Cool temps protected his quarry.

Scott was at the kitchen table when I arrived. He set his knife and the backstrap aside. We walked out back. The rack of a modest six point with long fronts and heavy beams, characteristic of his home range, lay in the yard. Several tines were broken, along with the bridge of his nose. Sitting atop a cliff-band, the elk had run straight at him. He practically had to shoot out of self defense. Once hit, the bull fell over the cliff ledge. A grizzly fed on the gut pile overnight but with the help of friends the meat was all packed out the following day.

Jeff sent me a text: “Just getting out of the woods”. I’d heard he had gotten an elk. Along with another friend they had packed out half of the animal the night before. It was three miles from the truck and he had to guide on the river that day. He was planning to hike in late that night to get the rest. Scott and a couple other friends, returning the favor, hiked in and packed out the elk instead, saving Jeff from a late night.

I was visiting Lander, Wyoming for a weekend. A town I had lived in for nearly a decade and where many of my closest friends still live. October is my favorite month of the year and my brief visit highlighted the best parts. The leaves had turned. A chill was in the morning air, followed by the warmth of the afternoon sun. My friends were harvesting elk. But beyond the elk all my friends were enthusiastically helping each other, sharing in the experience, telling their stories, and continuing a ritual that has become what I love most about Fall.